Why is Elon starting a Party?

What social science tells us about why Billionaires run for office

It was only a matter of time. Shut out of the political process. Openly fighting with the President. Elon Musk is launching the America Party: the richest man in the world nominally fighting for the little guy(/bro).

On the surface, this is could be the most credible outside challenge to America’s two party stranglehold. Musk’s got what matters most in modern politics: a hyper-recognizable personal brand and comfortably more money than either party. Plus, he’s the Lord of the Memes of Production.

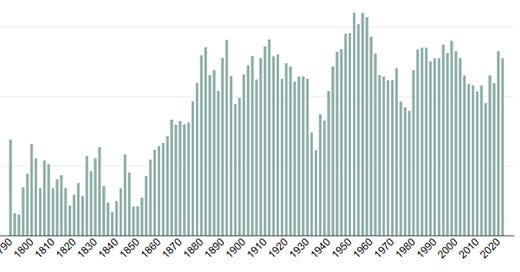

But this isn’t the break from political tradition it appears to be. Businesspeople have been entering electoral politics at a growing rate—not just as donors, but as candidates. We’re in what might be called America’s third wave of business-politicians.

I explore that rise in more detail in this longer breakdown at the home of Price of Power, but here are the key insights to understand Elon’s new attempted power grab.

How prevalent are business-politicians?

Nearly 30% of the U.S. Senate now comes from business backgrounds.

Roughly 32% of U.S. mayors have similar experience. In Russia, businesspeople ran in 35% of mayoral elections between 2007 and 2016—and won nearly a quarter.

But Musk isn’t just a businessperson. He’s a billionaire. And billionaires are in a league of their own when it comes to politics.

11.7% of billionaires globally have run for or held formal office. When you add informal roles—think affiliated but unofficial advisors a la DOGE—that number climbs above 15%. And they’re not just running: they’re winning. Only 8 out of 242 billionaire candidates lost. Interestingly, 6 of those 8 were American.

But the aggregate numbers don’t tell the full story - billionaires are far more likely to directly enter politics in autocratic settings, which America is increasingly resembling.

Why would the richest people on earth enter one of the least efficient professions?

The answer, across contexts, is protection and profit.

In China, Yue Hou documents that gaining office can act as an insurance policy. Legislator status sends a signal to overzealous regulators or commercial rivals: I’m connected. In Russia, businesspeople are more likely to run in regions with weaker institutions—where oversight is light and corruption harder to track.

We know political parties see business leaders as useful funders but that extends beyond donations. For example, in Zambia, being a business owner increases the likelihood of party recruitment by 56%. It’s not philanthropy or ideology—it’s mutual gain.

Because once they run, they often self-finance. 24% of U.S. business candidates for federal office put at least $1 million of their own money into their campaigns. That’s compared to just 4% of non-business candidates.

And their firms get involved too. Companies associated with business-candidates spend 6x more supporting them than they do for typical politicians.

Electoral office is profitable even for an already wealthy businessperson

In the U.S., the average stock bump for a company tied to a newly elected business-candidate is 1.4%—roughly $200 million in value. Peer firms in the same sector see gains too, as markets bet on favorable regulation. In Russia, business-connected firms that win office grow revenues by 60% and profit margins by 15%. They also become 40% more likely to win state contracts.

The logic is clear: for business elites, politics isn’t a new game—it’s a continuation of the same game. Elected office can be part of the toolkit to increase your business value.

There’s one major caveat to this playbook: it often doesn’t end well. For every tycoon-president, there’s an oligarch who overreached. Elon just needs to pray that he doesn’t turn into the next example of a billionaire taken down by a leader with autocratic ambitions.

Musk launching a party isn’t surprising. It’s statistically predictable. The question is whether voters recognize the underlying incentives.

For a deeper look at the research behind this trend, check out The Business Politician: Motives, Methods, and Private Gains.